Messages from Mya Dale: A eulogy

by B.E.

“I was richly blessed with the opportunity to get to know Mya,” writes B.E., “and I am compelled to share her story, as I understood it, so that the messages and lessons of her life do not fade away.” B.E. shares her memories of Mya Dale, in a eulogy which will be publicly read on B.E.’s behalf at the Fairview Block Party on Saturday, July 21.

“I was richly blessed with the opportunity to get to know Mya,” writes B.E., “and I am compelled to share her story, as I understood it, so that the messages and lessons of her life do not fade away.” B.E. shares her memories of Mya Dale, in a eulogy which will be publicly read on B.E.’s behalf at the Fairview Block Party on Saturday, July 21.

On June 29th I shared the handwritten draft of this eulogy and was asked not to read it at Mya’s memorial because, “people did not know her like that” and “they want to remember her as they knew her”, or words to that effect. I worked to revise it, to make it more “acceptable,” but the inconvenient truths are still here. I’ve added more for clarity and to share with you the woman I knew and loved, who yet calls me to action and I hope she calls you too.

* * *

I was richly blessed with the opportunity to get to know Mya and I am compelled to share her story, as I understood it, so that the messages and lessons of her life do not fade away.

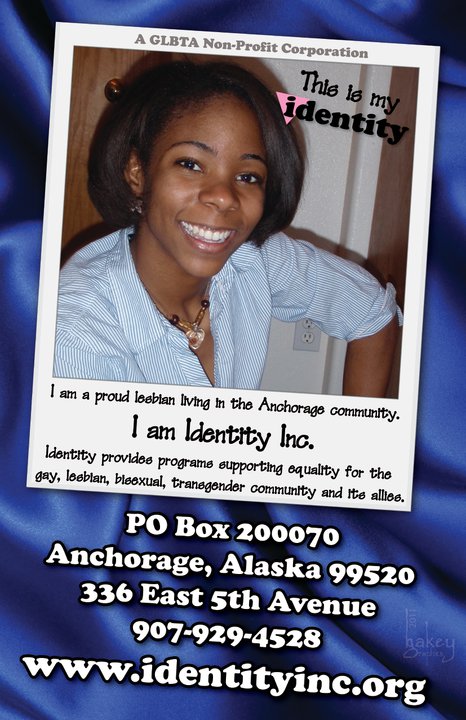

At 20, Mya bravely offered her open, childlike face to Identity Inc., the Gay and Lesbian Community Organization in Anchorage, to be displayed on circulated posters as an example of someone revealing a legitimate aspect of her identity. She had spent a significant amount of time in her life denying and suppressing this part of her. She’d hated herself, believing that she and her thoughts were dirty and evil and that neither God nor human kind would forgive her, but she had grown weary of hiding.

At 20, Mya bravely offered her open, childlike face to Identity Inc., the Gay and Lesbian Community Organization in Anchorage, to be displayed on circulated posters as an example of someone revealing a legitimate aspect of her identity. She had spent a significant amount of time in her life denying and suppressing this part of her. She’d hated herself, believing that she and her thoughts were dirty and evil and that neither God nor human kind would forgive her, but she had grown weary of hiding.

The only child of a single military member who was required to be away from home at intervals, leaving her with family and friends, Mya had grown up fearful of abandonment. She strove to do everything right in order to earn love and favor: dress “girlie”, be a devout Christian, perform exceptionally as a student and athlete. All Mya wanted was acceptance, from herself and others as the person she truly was.

Mya spoke of growing up in Alaska feeling instead, often isolated from her peers, most of whom were not of color. At times she struggled in social graces and academics and suspected that she was being graded more harshly than her white counterparts, which caused her to feel inferior, helpless and furious.

As a result she tried diminishing the African American part of her identity. At times she avoided and felt she could not connect with the other few faces like her own in Anchorage due to the negative stereotypes with which she was most familiar, rather than having had a more broad, positive immersion in the history and community of African American people, that might have helped her be comfortable in her own skin. She would continue to be leery and ashamed of representations and caricatures of black people in television and film as those who could be presumed promiscuous, simple, comical and criminal. Mya wanted no part of this false identity.

As she grew, Mya was further disturbed by what she thought was God’s betrayal, having made her the seemingly lowest of all, both African American and female. She resented being “trapped” in the female body, which she understood was most often “weak,” “emotional,” and “hapless”. She furtively wished that she had been born male, and believed in fact that this was what she was meant to have been.

These circumstances that Mya felt cursed by were intensified by her painful fear of rejection and embarrassment for failure. The fears followed her to college at the University of Alaska Anchorage (UAA) where she strained against a shy disposition to fit in, while maintaining good academic standing. She finally buckled under these and other emotional pressures and had to leave school for a time.

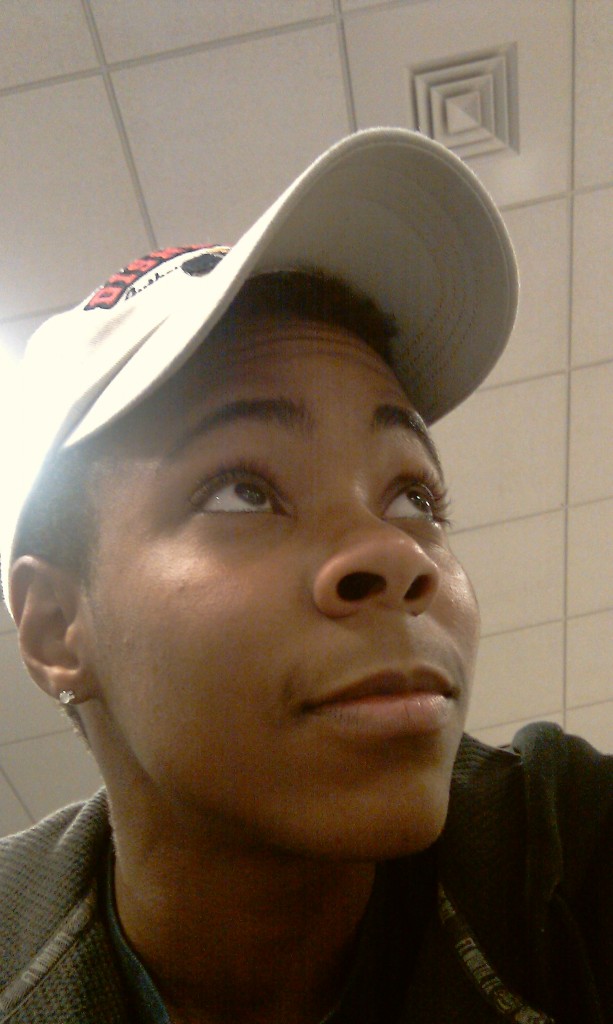

After Mya returned she was determined to be truer to herself and began to dress less feminine. She hid her chemically straightened hair under caps, eventually cutting it off to reveal her own curly natural. She began to deliberately set aside her fierce athletic competitiveness, associating it with her drive to be perfect in order to gain approval.

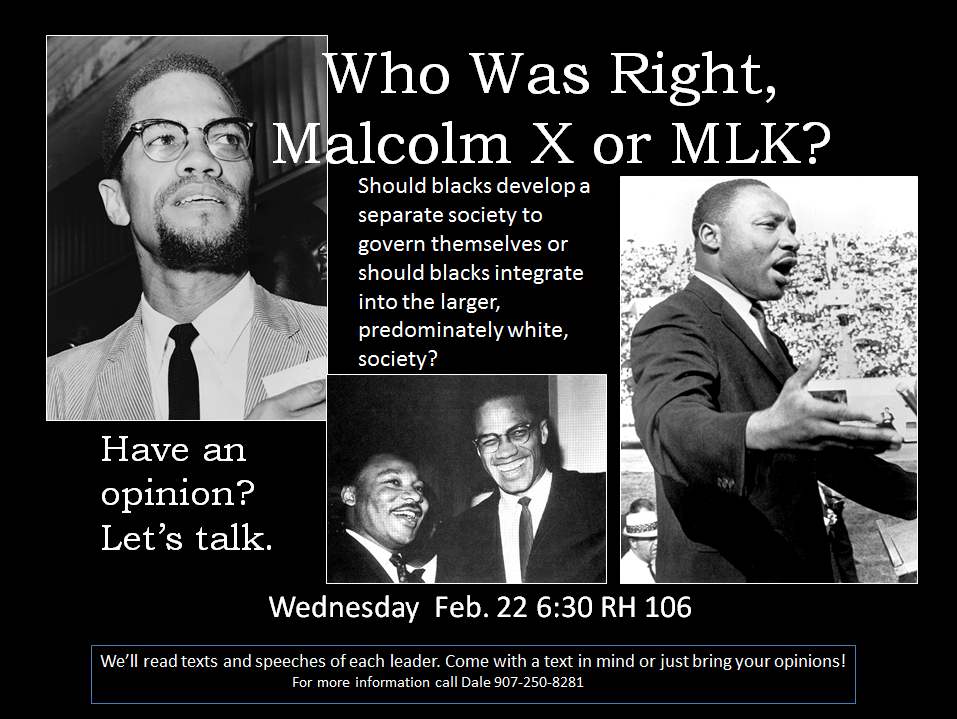

Mya learned of civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, who was both African American and gay, and she was encouraged. Over the last year (2011–12), she read W.E.B Dubois’, The Souls of Black Folk

Mya learned of civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, who was both African American and gay, and she was encouraged. Over the last year (2011–12), she read W.E.B Dubois’, The Souls of Black Folk and The Autobiography of Malcolm X

, books that I pray will be added to the UAA core curriculum, and the Anchorage School District required study, along with others like them. If we did this on a national level, it could change our society.

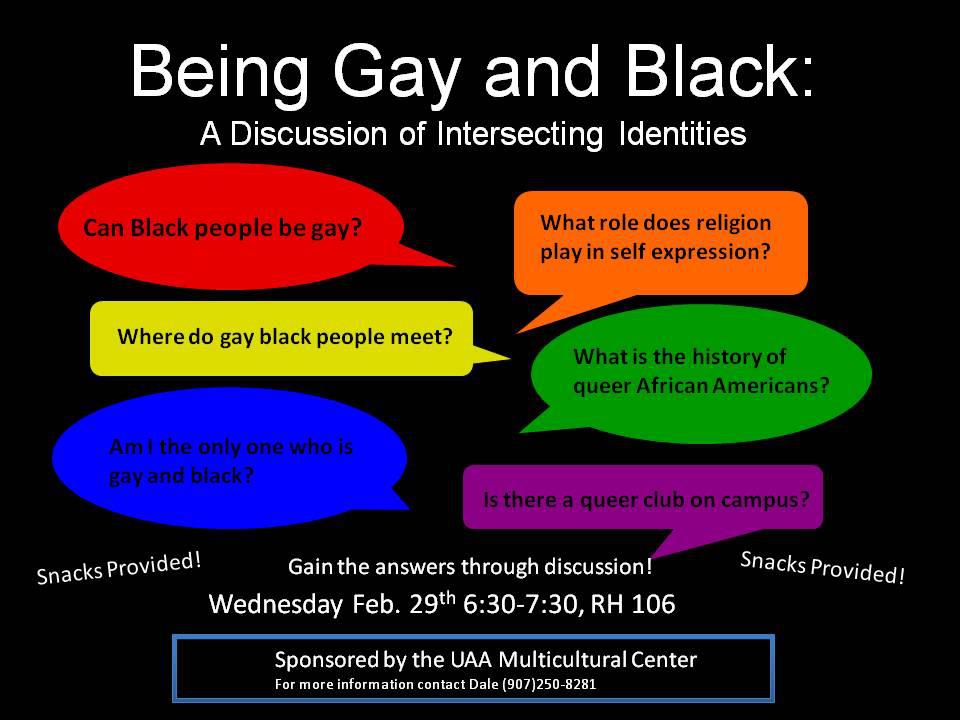

The explanations of African American trial, talent and triumph in these books helped Mya begin to better understand this part of her identity and begin to be proud. Her newfound confidence led her to host stimulating discussion panels at UAA inviting students of various backgrounds to intellectually consider specific African American experience, contributions, and thought.

The explanations of African American trial, talent and triumph in these books helped Mya begin to better understand this part of her identity and begin to be proud. Her newfound confidence led her to host stimulating discussion panels at UAA inviting students of various backgrounds to intellectually consider specific African American experience, contributions, and thought.

Mya fought to come to terms with all of her identities, noting that what she began to identify with often faced prejudice, suppression and invisibility: being African American, being a woman, loving women and finally, disability. Though easily wounded and frightened, Mya kept pushing the envelope to speak up for herself and others when she encountered what she thought was bias toward any of these.

Mya recognized that those with so-called disabilities were further challenged with how to gain “normal” acceptance in the overlapping groups to which they belonged such as LGBT, youth, or of color. She often commented on disability, challenging the “otherness” placed upon it and the resultant abandonment possibly felt by survivors who, like her, just wanted to be accepted and treated with the same respect as everyone else, not as if they were “special.” She challenged herself and fellow students by spending school days at UAA confined to a wheel chair. She was struck by how frightening it had been to her.

She made it a point to reach out on a personal level to people who were disabled or “different”, even in dating. She became fascinated with the challenges of the deaf. She strove to understand this world and had aspirations of becoming an interpreter.

Mya arranged a meaningful forum on disability during the 2011 Anchorage Pride Conference to draw out perceptions, stigmas and learned behaviors. Whether or not LGBT persons who were also challenged physically or mentally had a lesser chance for love than others was also important to Mya.

Notably, she was careful not to speak of her own challenges, the almost invisible emotional turmoil that she had been battling for years, due in part to childhood trauma and the lingering self loathing and doubt.

I did not understand how damaging and deadly this pain had become. I never allowed myself to think of her as ill. I was in denial and ignorant. Now I am learning more about mental health challenges and am committed to getting help wrestling my own demons, as well as raising awareness, as she strove to do.

I did not understand how damaging and deadly this pain had become. I never allowed myself to think of her as ill. I was in denial and ignorant. Now I am learning more about mental health challenges and am committed to getting help wrestling my own demons, as well as raising awareness, as she strove to do.

The quiet side of Mya wrote incessantly. Some poetry and journaling to tell God her pain, or just lay things out. She said she did not consider herself a poet and instead wrote because she had to, comparing writing to going to the bathroom.

She was intent at drawing and art. She drew pictures of people’s faces and variant body types. She drew her mother’s name and her own She made careful sketches in cartoon frames to record often frightening images depicting her internal struggles.

At 21, she seemed at times to have the face and stature of a tall child, which she didn’t’ prefer, but like a tall child she often lay outstretched on the carpet surrounded by craft items making her own greeting cards out of construction paper, markers, glue and tape. They were lovely, original creations that she used to say, ‘thank you’.

The lighter, bubbly side of Mya was the side I saw run up and across a picnic table in excitement after learning how to do perform a rescue carry. It was the side that loved to be taken piggyback riding and wanted to take you too. The side that had a made-up funky skip-walk when she was eager, the side that squealed aloud and laughed like a playground full of children – that babbling brook, innocent sound that never grows old. The side that bounced up and down and circled you at once with anticipation, one that imitated instruments, made funny faces, turned flips and cartwheels. She’d practiced break dancing, but achieving the headstands and other moves was challenging, serious business. Not for fun.

Aside from such technical moves, Mya’s lighter side loved to just dance! And when she danced, her face danced! Mouth open, long lashed eyes aglow, parroting lyrics, filled with theatrical expression. She opened wide her arms, pointed her toes, kicked her legs out and spun, all five foot, three inches of her in motion! As if to dance away all the day’s pain, all the night’s sleeplessness and fear.

Several of Mya’s messages for us resonate:

- Deliberately reach out to everyone we see, no matter their color, orientation or ability. Help everyone we see feel Safe, Accepted and Normal.

- Mental Illness is real and often almost invisible. Recognize it as a possibility while not a negative. Support others in getting help.

- Multicultural and Diverse is not an identity. No matter how few, African Americans and those around us, must be deliberately educated about who our forefathers and mothers were before slavery, in spite of it, and after, so that we too may have a sense of self.

- Demonstrate that we believe women are as important, worthy, strong and good as men.

- Live each day with a purpose. Do what you can to make a difference.

- And while we are doing all of this, as the song says, if we get the chance…dance!

Photos of Mya Dale courtesy B.E. “I am Identity Inc.” poster courtesy Identity.

Related posts: