Since Sunday night’s announcement by President Obama that U.S. forces had killed Osama bin Laden, I’ve read a lot of stuff about whether or not it’s okay or moral to be glad about his death or to celebrate it.

Since Sunday night’s announcement by President Obama that U.S. forces had killed Osama bin Laden, I’ve read a lot of stuff about whether or not it’s okay or moral to be glad about his death or to celebrate it.

My own reaction was a combination of glad he can no longer bring harm, but also pensive & mournful about the harm his followers & sympathizers, as well as his detractors & enemies, have already caused & will continue to cause. That, or something like it, seems to have been a pretty common reaction… a sense of relief or release coupled with sadness, as at the end of a long ordeal. One of Andrew Sullivan’s readers:

You know the odd thing? I’m not feeling … ecstatic. I’m just feeling a kind of sad relief. I recall reading Miep Gies‘ book about her role in hiding the Frank family. When it was declared that there was victory in Europe, she said that people in Holland were hysterical and tearing into the streets to celebrate. But her husband, who’d risked so much working in the resistance movement, just sat quietly. She asked if they should go out and celebrate with everyone. He said no. It seems too much had happened. Too much pain witnessed. Too much death as a result. He was tired. It was enough to just know that it was finally over. I think I know what he meant.

I pray tonight for the souls of the departed who died that awful day, and all their family members and friends. I pray for the souls of those great Americans who resisted on Flight 93. I pray for all those who have died in the two wars that followed this atrocity. As a Christian, I am also required to pray for the soul of Osama bin Laden. Yes, even him.

Some conservative Christian leaders quoted a biblical caution:

Do not rejoice when your enemies fall, and do not let your heart be glad when they stumble. (Proverbs 24:17)

(Never mind that there are also biblical verses that celebrate the deaths of enemies.)

Quote added 12:05 PM: His Holiness the Dalai Lama today in Los Angeles, per the Los Angeles Times:

As a human being, Bin Laden may have deserved compassion and even forgiveness, the Dalai Lama said in answer to a question about the assassination of the Al Qaeda leader. But, he said, “Forgiveness doesn’t mean forget what happened. … If something is serious and it is necessary to take counter-measures, you have to take counter-measures.”

Here’s my take.

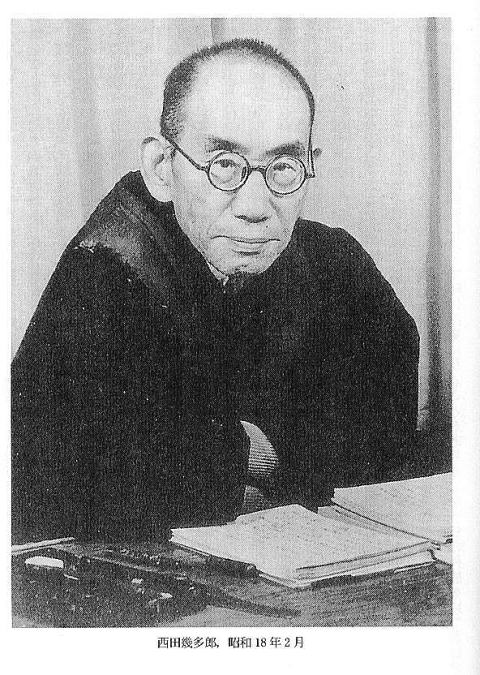

In 1979 I wrote a paper in college in which I quoted an article from a Japanese academic journal from 1970. (In translation — I didn’t know Japanese then, & I don’t know it now.) The article was “Religious Consciousness and the Logic of the Prajnaparamita Sutra” by Nishida Kitarō (1870–1945), an important Japanese philosopher. I still have my college paper somewhere hereabouts, but damned if I’m going to track it down in the middle of the night. However, I still have the quote handy because I wrote about it on an email discussion list I was part of in 1998.

(Yes: I have email archives that go back that far — as far back, in fact, to 1994. Besides having an MFA in Creative Writing & a B.A. in Religion, I am also a geek of the email-retentive variety.)

Let’s assume that there is not only Him and man represented in the quote which follows herewith, but also Her and woman:

The absolute God must include absolute negation within Himself. It must be God who can descend into absolute evil. It is a truly absolute God by being God who saves the wicked and the immoral. The highest form must be one which transforms the lowest matter into form. Absolute Agape must reach even to the absolutely evil person. In the relationship of inverse polarity, God must be hidden even within the heart of the absolutely evil man. A God who merely judges is not an absolute God. But this does not mean that God looks indifferently at good and evil….

I don’t have any illusions of being absolute God in my abilities or desires to love, agape-wise, the absolutely evil person. Yet to the extent that I can recall my own wrongdoings and, by extrapolation, imagine my way into the skin of someone further along the spectrum towards evil than I (presumably!) am — well. I’m not sure how far I can go. But I can go at least a ways in that direction. Usually I can find there a person who is recognizably human, and recognizably suffering, and recognize my own humanity and suffering in that person.

Sometimes I can’t imagine that far. Yet I’m certain that illimitable god, the truly absolute God by being God, can.

I have been a universalist (in a nondenominational sense) for a long time, in at least some degree since late junior high when I put behind me the belief that there is only one way to God. Universalist: someone who believes that all will be reconciled to god: in my case because if, as I believe, god is the universe and everything in it, then no one is completely separable from god. God is in our breath & our bones, our very substance — body, mind, & spirit.

I think that conviction was implicit in my understanding as early as back then, in late junior high; but it was probably my 1979 encounter with Nishida Kitarō which brought it explicitly to my consciousness. (A big thank you to my professor, T. James Kodera at Wellesley College, who put Nishida’s article, & so much else, in my hands.) I don’t have that article still, but I recall Nishida saying something about how (in the Christian scheme of things) God is seen as absolute good, Satan as absolute evil: but that by virtue of them being absolutes in opposition to one another, that also puts them in relationship with one another. They are not, in other words, flung off from each other, but are inextricably tied to one another, like the two ends of a ruler, or two ends of a rope in some cosmic tug-of-war. With God, of course, on the winning side, such that even Satan will ultimately be pulled over to the side of good.

Actually, I can learn much more from Nishida now, because I recently ordered a couple of books by/about him, which are sitting at my bedside as part of that rather large pile of books to be read. And in fact one of these books, Last Writings: Nothingness and the Religious Worldview, appears to incorporate Nishida’s discussion in the article I encountered in 1979.

But I’ll get to that later. Right now its enough to know that in 1979 I found Nishida’s argument persuasive, and I still find it so today.

In the relationship of inverse polarity, God must be hidden even within the heart of the absolutely evil man.

And so it was with a sense of recognition that I read a blog post that a Facebook friend linked to yesterday. It’s a post by Susan Piver called “Osama bin Laden is dead. One Buddhist’s response.” Here’s the passage that particularly stood out for me:

Was there even a hint of vengefulness or gladness at Osama bin Laden’s death? If so, that is a real problem. Whatever suffering he may have experienced cannot reverse even one moment of the suffering he caused. If you believe his death is a form of compensation, you are deluded.

There has been an outpouring of misdirected jubilation, as if a contest had been won. Nothing has been won. Unlike winning a sporting event, this doesn’t mean that our team has triumphed. Far from it. There is only one team and it is us. When those of us (especially our leaders) who now foment violence choose instead to try to create peace, then we will truly have cause for celebration.

One of us is gone, one apparently horrific, terrible, vicious one of us…is gone. I don’t feel regret for him or about this. I’m regretful for the rest of us who are now left thinking that this is a cause for celebration. It is not. It is a cause for sorrow at our continued inability to realize that there is no such thing as us and them; that whatever we do to cause harm to one will harm us all. [emphasis added]

There is only one team and it is us. Not just a Buddhist sentiment: I agree with her. For whatever reason, some twistedness took hold of Osama bin Laden, & in thus he wrought evil upon evil. All the same, he is — he was — one of us, as much as were all the people who lost their lives or loved ones in consequence of his twistedness.

But while I myself can’t bring myself to celebrate bin Laden’s death, precisely, nor do I regret it. Nor do I begrudge or judge those who do celebrate it.

A God who merely judges is not an absolute God. But this does not mean that God looks indifferently at good and evil….

That’s all the further I got with the quote when I cited it in an email in 1998. But what’s Nishida say after the ellipsis? In Nishida’s Last Writings, the same or a similar passage (with some differences — whether because Nishida refined his language, or because it had a different translator, I don’t know) reads:

A God who merely judges the good and the bad is not truly absolute. But this does not mean that God looks indifferently at good and evil. To conceive of God as a supremely indifferent perfection does not square with the testimony of our spirit. [emphasis added]

It’s the testimony of our spirit that leads some of us to raucous celebration of the death of the terrorist who did so much evil — just as many must have celebrated the death of Hitler, Stalin, Pol Pot.

As for me, the testimony of my spirit is that doing good — being in right relationship with and taking right action toward myself and others and this grand and infinite universe of which we all are part — is reward and motivation in itself to continue to do good. I feel at peace & easy in my skin when I do good. Whereas to do wrong is its own punishment: it makes me feel horrible to hate, & even worse to harm others — to harm is a hell that also harms me: it twists me, it makes me ugly, it makes me a stain on the face of creation & a stink in my own nostrils.

That’s what Osama bin Laden did to himself, however much he may have rationalized that such twistedness was demanded of him by God. Few of us who suffered from the evil he did will ever be able to forgive him. If illimitable & absolute god is not merely a judge — yet god does judge. And so, part & parcel of god, do we.

And sometimes the testimony of our spirit demands that we take ruthless action against those whose evil would continue to spread, if we did not stop them.

In that sense, I am glad that Osama bin Laden is dead. I find myself untroubled to know it.

Meanwhile, I also agree with what my niece, who’s living in New York City now, wrote on her Facebook wall yesterday:

maybe folks think it’s tacky to be happy about bin Laden’s death, but I think it’s even tackier to criticize the NYC folks’ feelings about it.

2 Responses to On celebrating the death of bin Laden